In 1906, wealthy socialite Harry K. Thaw shot and killed the architect Stanford White. This book, a vanity-press publication which appeared two decades later, is Thaw's attempt to justify his crime. On that score, and indeed on every other, it is a dismal failure, as Thaw's peculiarities of mind make his writing arduous and unrewarding to read.

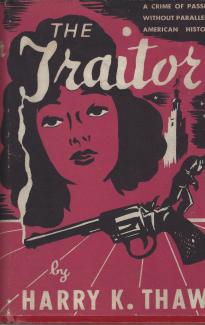

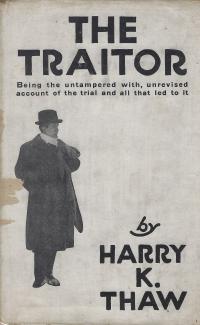

My copy, and I don't know if this is usual, has two dust jackets, apparently aimed at different markets. One has a luridly coloured, trashy design with a gun and woman's face: "A Crime of Passion Without Parallel in American History!" it promises. The other is more sober and shows Thaw standing thoughtfully, dressed in a winter coat and sucking on a pipe. This, presumably, was the one you could leave on your coffee table without attracting the disapproval of a visiting bishop or maiden aunt.

Thaw justified his shooting of White by claiming that White was a serial rapist who used his social standing to gain access to young women whom he then drugged and raped. Thaw's own wife, Evelyn, was one of White's victims.

Had Thaw made White and his misdeeds the main subject of his book, he might have gained the readers' sympathy, but unwisely he chose to spend a large part of his account, most of the first third of the book in fact, describing his life prior to meeting Evelyn, a life which seems to have consisted entirely of dinners with other wealthy folk and prolonged holidays in Europe, and which is recounted by Thaw in a curiously juvenile style.

Next Madrid. Modern and only looked at the pictures again. Marvelous pictures.

Then to Paris. The end of April everything starts and is most cheerful for an old man, a young man and everyone between, if you forget that Paris can't be improved for you can't change it. My only notion was being angry as everyone could speak and hear and I couldn’t. Until I got teachers. Day after day if early you got to the Bois, then lunch and more restaurants than now, and a dozen very good. Then to the races, Longchamps or Auteuil. Then all sorts of places for tea only none use tea, even in people’s houses. Probably less than half the time I stopped in people’s houses, and more in the Chateau de Madrid or Armeninville. Next dinners, and no matter if a hundred or alone, dinner is worthwhile. There were only two hours afterwards that were wasted in Paris when you have to go to the theatres or bouffes, or you could hear the singers of the Opera or Opera Comique. But I would rather have something else. Except the first time, when La Boheme came and the Sieur de Vergy, that I liked. and of course Offenbachs [sic].

What makes Thaw's way of writing even odder is the degree to which it varies depending on what he is writing about. The preceding passage is typical of those that depict his travels and socialising, but when, suddenly, he turns to the subject of a mountaineering expedition in the Alps, it is as if another hand, one belonging to a calmer and more mature individual, has grasped his pen and taken over.

Next morning, very early, we started out of town and across the steppe towards the base of the mountains. On our left the high range disappeared towards the southeast, but to the right, above the foothills, mass on mass of snowy summits soared; Ouchba and Dyke-Taou, and far westward, possibly Elbruez, the highest mountain in Europe; while in front stood Mt. Kazbek.

In two hours we reached the foot of the mountains at Balta, and passing a fort, entered the Gorge of Djerakhovakoic. Another name is the “Gorge of the Devil.” Nothing but stone; stony the bed of the tumbling river, stone the edge of the road, and the ragged cliffs sloping up and up, marked by tours de guet, to where the topmost pinnacles rose like watch-towers all along the ragged wall of rock. Like a guardhouse of stone, it closes the road from Asia into Europe. The fantastic jutting rocks and perhaps the glancing lights reflected from all the stone surfaces, gave at first an almost festive look; but as we crawled upward, the hard desolation became more and more impressive. Not lonely like steppe or desert, nor dismal like a cave, but for absolute hardness from top to bottom I have never seen the equal of those grey walls, mounting skyward to their jagged rims.

If there were more of this, and less of the incomprehensible social life of a tiny elite, perhaps one could warm to Thaw, so to speak, but as it is we get page after page of this sort of thing:

The reason I wanted to leave James Henry Smith’s party was that I began a big dinner. I did not want to; I said, "I'm not a New Yorker," but very good friends insisted that I had been there long enough, even if I had been an Englishman or a Russian. Mr. and Mrs. Ogden Mills and Mrs. Ogden Goelet accepted, also Mrs. Paget and the Burdens, Mrs. Fish, the Willie Jays, Mr. and Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt (though I don’t think the General ever knew what happened). I merely walked in and wanted to walk out unnoticed except by Smith because — note because — he had not asked me for his dinner. Naturally, if I had danced with Miss May Van Alen there would have been no trouble. But Lehr pushed me into another instead, and at that moment I wanted to be ill. Afterwards I wished it even more. I don’t think one-tenth of you bother about this impending shindig. I knew it would be coming.

The contrast of prose style is so great that one might suspect that Thaw plagiarised the mountaineering passages from some travel book in his possession, but if he did, it's not one that's accessible online .

We are now nearly 100 pages in, and still no sex or violence. Hurry up, Harry!

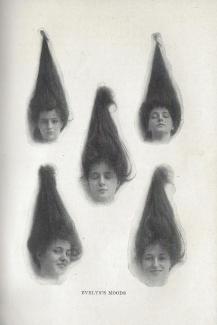

Things begin to pick up with Thaw first encountering Evelyn Nesbit as a chorus girl in a Broadway show called "Floradora". He began to pursue her despite the obstacles created by her mother's opposition and his own social calendar which this time took him to Washington and another round of prestigious dinners.

We won't tarry over Lord Hartford nor over Lady Paget's later comings, nor even of Miss Gwendoline Foukes, nor Roosevelt's very pretty daughter.

Evelyn, who had been ill with appendicitis, travelled with her mother to Paris, where she and Thaw reunited, and he asked her to marry him. Her mother was opposed - understandably as Evelyn was still a minor and Thaw was 30 - but he induced Evelyn to accompany him on his European travels. When they got back to Paris after some months Evelyn went back to the US with her mother. Thaw does not explain what had happened between them, but it is clear there was a rift. Thaw's description of this period is as unreliable as one would expect, but glimpses of the actuality come through, as when Thaw recounts a meeting with Evelyn at a hotel in New York, where he'd gone to see her against the advice of two of his friends, Longfellow and Warren:

Warren sat in one corner in her room and Evelyn and I had a talk. She said she didn't want me, but from her looks I knew better. I said "Poor little Evelyn" and told her that she should not be asinine. Then Warren came and talked, and then I went to the Walcott Hotel.

She sent all my clothes and in them was an ivory nail file; I knew by that everything was all right, but Longfellow and Warren had prevailed on me not to see her until Christmas, her eighteenth birthday, 1903.

Thaw persisted in his pursuit over the next few years and they were married in 1905. Having learned from Evelyn of her abuse at the hands of Stanford White, Thaw became increasingly obsessed with White and enacting revenge on him. On June 25, 1906, by sheer chance both White and Thaw were both at a theatrical performance on the rooftop terrace at Madison Square Garden, and when Thaw saw White he seized the opportunity.

There I saw him thirty feet in front of me, and as he watched the stage he saw me. I walked towards him and about fifteen feet away I took out my revolver. He knew me and he was rising and held his right hand towards, I think, his gun, and I wanted to let him try, but who was next! A man, a dozen men might have maimed me, cut off the light, allowed him to escape and rape more American girls as he had; too many, too many as he ruined Evelyn.

Half-rising he gazed at me malignantly. I shot him twelve feet away. I felt sure he was dead. But I wanted to take no chances, I walked toward him, and fired two more shots. He dropped.

I looked to see if any feel should attack me; there were two bullets left, if needed. Instead all the people moved and moved so far, surging to the end of the roof, that I feared some might be forced to fall, toppling to the street eighty feet below, so I slowly raised the gun above my head, and turned rather fast, yet not enough to alarm anyone, and went back the same way as I had taken.

Some men observing that they were safe, I walked and handed the pistol to one of them. Then straight to Evelyn. She uttered a cry: "My God, Harry, what have you done?" I held her close and told her: "It is all right, dearie, I have probably saved your life." Then I kissed her.

Thaw was arrested and imprisoned without bail. The case went to trial the following year. His account of proceedings is bizarre and hard to understand, largely because it is largely concerned not with the murder itself but with the actions of his defense attorney, Lewis Delafield, the "Traitor" of the book's title. Thaw cannot even bring himself to name Delafield, whom, he calls "more venomous than White", "contemptible", and "a weasy [sic] little ferret with a grey goatee". Delafield's offence was that he attempted to get Thaw off on the basis of insanity, employing a team of "alienists" (psychiatrists) to provide testimony as to Thaw's unsound mental state. Thaw, who wanted his killing of White to be seen as a justified crime of passion, not the action of a lunatic, could not countenance Delafield's strategy.

Thaw's other concern is with the testimony of Evelyn, whom he paints as bravely defending him against the District Attorney, William Travers Jerome. As part of his case against Thaw, Jerome had the lawyer Abe Hummel testify that in 1903, after she had returned from Europe she had sworn an affadavit in Hummel's office that Thaw had viciously assaulted her with a whip while they were staying together in an Austrian castle. Thaw doesn't mention the allegation of assault, merely that the affadavit attempted to blacken his character, but says that Hummel was a tool of Stanford White, employed to fabricate a false statement to which Evelyn would put her signature. In court, Evelyn resisted all attempts by Jerome to get her to speak against Thaw, leading some commentators to guess that she had been paid off by Thaw's family.

Did his wealth afford him special treatment? Thaw would have us think not, as he says at one point in a typically incoherent aside:

Might I change for a minute? There is now a cheerful man named Smith, the Governor. He is a splendid man, but he had a notion that I was rich and that I had a great advantage compared with people he knew, who were very poor, and I’m certain millions must have thought the same way as Mr. Smith. Yet you might know that, after we were betrayed, we were far worse off than any poor man anywhere.

Suppose poor Evelyn and I had a false lawyer, would he beat us? Never, for too many newspapers would see, precisely as that Editor of the Evening Journal knew. We lost more than any poor people, as they would be saved, for even their poor acquaintances would have saved them, for they would see they were “bilked.” But our Traitor was so respectable on top and he hired money (every cent of it mine), and men who were well known, and because Evelyn and I were rich, none ever crushed them; only that Editor suspected. It was not Olcott’s fault, he was fooled like us. It was only the great majority of regular people and Evelyn and I beat the Traitor, but our result from his cowardly cheating kept on and on.

(Judge Olcott was one of Thaw's lawyers; "Smith" was the foreman of the jury.)

You will not learn from Thaw's book that there were two trials, nor that at the second one he pleaded guilty by reason of temporary insanity, nor that he and Evelyn were estranged and later divorced in 1915. You will also not learn that he was sentenced to be detained for life at the Matteawan State Hospital for the Criminally Insane, nor that he fled from there to Canada, eventually returning and winning his freedom after another jury trial found him no longer insane. Despite this verdict, a year later in 1916 he violently assaulted a nineteen-year old called Frederick Gump with a whip, in much the same manner as Evelyn Nesbit had reported in the supposedly fabricated Hummel affadavit. For the assault on Gump, Thaw was again sent to a high security asylum, where he remained until 1924.

Even without all these damning details, Thaw's attempt to paint himself as purely a high-minded defender of the virtue of young women is defeated by its sheer oddity. Leaving aside the all superfluous reports of fancy dinners and the often fractured prose, when you call your true crime book "The Traitor", but then fail to say who "The Traitor" was, readers will be justified in giving it the thumbs down.

Leave a comment